The French filmmaker Louis Malle said, in his series, Phantom India, that while in India he often felt like he was “dreaming with his eyes open.” That’s a nice way of putting it–the feeling that everything was just different enough or just striking enough, not to seem real.

Mumbai (Bombay)

Almost as soon as we arrived we realized that—without intending to—we had engaged in a footrace with a couple of our fellow passengers to get to customs. A genuine race: the older, Indian couple kept passing us and then getting stopped by some obstacle or another and then passing again, looking back with smirks! I wasn’t sure how exactly we’d engaged in the competition, but it was the first of many times we would feel like our presence was providing entertainment.

At customs, we had our first encounter with the Indian head nod or bobble (Indians nod their heads left and right rather than up and down to say yes, but also as a greeting, and seemingly in multiple contexts). Our books had warned us not to misinterpret it as an insult. “And why would we?” we wondered. The reason for forewarning became more clear as the agent would nod his head after we spoke… it really took us aback. We could see how one could feel mocked. As it was, it seemed only charming.

We were lucky enough to have a room waiting for us at the JW Marriott in Juhu, courtesy of Aron’s parents. After the chaos of the flight—all the exhausting efforts made to leave New York—it was so nice to be met at the airport by a driver from the hotel.

To back up a bit (though I won’t go into detail), the ash cloud created by the volcanic eruption in Iceland cost us one day of our trip and an error made by Continental cost us a second. We actually got to the airport, had checked our bags, and were at the gate in-line to board before we were informed that we had lost our seats on the flight and that we had been rebooked for two days later–leaving Sunday rather than Friday. We were heartbroken and angry at the same time. After two more trips back and forth between the airport and our apartment over the next two days to get our luggage back and work out the details of the flight, we made it on the plane. We jotted down some notes about what happened, and then did our best to move on and enjoy the rest of our (now 10-day) trip. But we had to cut our time in Mumbai drastically and we lost a day in Udaipur as well. Continental eventually tried to make things right, but not without significant efforts on our part. And I don’t think that either of us believed we would actually make it to India until the plane touched down and the captain announced that we had landed in Mumbai.

After getting our bags, we stepped out of the terminal, into the heat, and looked out onto a sea of name-placards. I’d never seen such a crowd. We found our hotel’s name, were shown to a car, and were soon on the road. Cars and motorcycles darted around and squeezed past us. Throngs of people on their way to a temple for a religious event walked barefoot (part of the ceremony) beside us on the road. The classic yellow-and-black taxis seemed small and so surreal after having seen them so many times in pictures.

There was definitely a “pinch-me” feeling that we both shared.

The Marriott had upgraded us to a suite and agreed to a late checkout; we dropped off our bags and went back down to the concierge to get their insight on how best to get in and out of the city quickly. A friend of mine from graduate school, Pashmina, had set me up with tons of great suggestions for the city, and I had marked up maps of Mumbai in preparation for the three days we were supposed to have there; we knew we had to leave most of the suggestions behind, but were determined to still fit in as much as possible. That said, we’d been warned that traffic could be a real obstacle and could significantly eat into our time.

I was hoping that the train might be an option, but we were warned repeatedly that the commuter train was, “the way we get around,” but was not right for visitors. “Take a taxi,” they recommended. We kept trying to figure out exactly why this was and didn’t want to be dissuaded if the train were at all viable. Finally, when they learned that we would be traveling at off-peak hours, they decided we could handle it.

We went back to the room, took a bath, enjoyed some welcome beers and snacks, and then settled in for what by then amounted to (and I’m not exaggerating) a mere hour-long nap.

Just before sunrise, we caught a rickshaw outside the hotel and went to the nearest express train station. We pulled up to some ramshackle buildings—still in the dark—and our driver pointed “that way.” I’ll admit I felt a little nervous at first; I think all the warnings had me on edge, and here we were, beating the light, and I didn’t see any trains. But as soon as we turned the corner and I saw the tracks, I felt better. We bought our tickets with no problem. Finding the platform, on the other hand, was more difficult, and we crossed back and forth over the tracks before someone gave us directions. When we saw the train arriving, we ran to find the nearest first-class cabin; not knowing how long it would sit at the station, we wanted to be ready to jump on at any moment. As it turned out, we made it with plenty of time to spare.

We loved it immediately. We were surprised to find the cabin nearly empty, with just a few men on benches; we stood by the hanging hand supports and caught the breeze from the many opens doors and windows. The second-class car seemed slightly more crowded—although neither was filled due to the early hour.

We passed other trains, more busy than ours, and alternated between ducking out of their way and sticking our heads out, looking forward.

I’m sure I’ve never seen so many men emptying their bowels or urinating as I did over the next 40 minutes. The train tracks were clearly used as the local latrine, and paper trash littered their edges so as to sometimes cover the ground completely. Still, for the most part, the wind blowing through the car made it such that it was an assault only to the eyes.

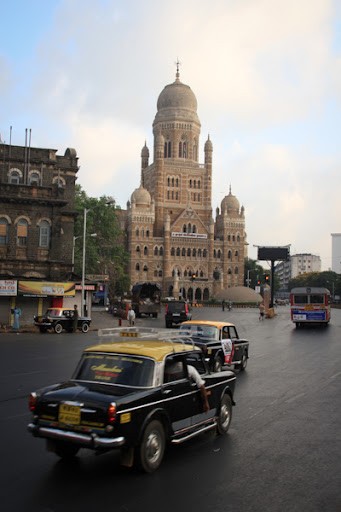

Despite some of the unpleasant aspects of riding past the outer slum districts, I was almost disappointed when we arrived at Victoria Terminus (now called Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus). Looking back on it now, our train ride was probably one of our favorite parts of our visit to Mumbai. It was such a perfect and fascinating introduction to India: women-only train cars; space designated for handicapped riders and patients with cancer (denoted by a picture of a crab, of course); men dressed in drab business-casual attire and headed to work; colorful women carrying large piles of goods on their heads; chai-wallahs starting their day; bright concession stands and vendors opening clasped tin dishes and setting up for sales; and vast VT station—just beginning to get crowded, but for now filled only with beams of morning light filtering down through skylights.

Apparently the train station is the second-most photographed building in India (after the Taj Mahal, of course). Despite some scaffolding, we could see why: We walked around the station, taking in its high domes and intricate European-style stone work. It looked great in the context of the classic black-and-yellow taxis that moved in and out of our total view. Traffic was still fairly light, so we were actually able to cross the traffic circle in front of the station (though that would not be so for long).

We hired a rickshaw for a ride over to the Gate of India—from where the British left India in 1948. We looked around, walking past a dozen or so men with fancy Nikon cameras and examples of how one could pose beside the adjacent Taj hotel (pretending to lift its dome with a pinch). The growing heat and humidity—and our curiosity—sent us looking inside. Passing through security, we looked around the lobby (which they were remodeling in the wake of the 2008 attack on the hotel), and peered into one guest-only section—a courtyard with a pool. The most wonderful smells were coming from the breakfast room and we realized that we were very sorry we had to miss the breakfast that came with our room; I’m sure it would have been delicious. The stop gave us the perfect opportunity to reorganize and cool off a bit.

A colleague had recommended a juice spot near the hotel; I’m not sure we found the exact one, but we spotted a crowd of men gathered around one take-away counter, eating breakfast. With some pointing and inquisitive smiles, Aron was offered some bread cutlet with chilies and I ordered us some fruit juices—sweet lime (like orange juice) and mango juice. We couldn’t have ours with ice, so the mango was more warm and syrupy than refreshing, but it was absolutely fantastic. Aron also couldn’t resist a yellow-lentil cake with loose spices and salted chili peppers on the side. The savory cake was delicious: salty and herbaceous. The peppers were too spicy for me, but Aron attacked them with each bite of cake. It wasn’t long before his eyes were watering and his voice grew hoarse. The vendors loved this, of course, and kept giving him more. He insisted that he had just swallowed wrong, and kept eating the chilies. We were all laughing and I wasn’t sure what to believe.

We plotted a course that would take us past the Prince of Wales Museum and around Oval Maiden, past the University. Our limited time precluded our visiting any museums, but I was excited to see young boys in white, practicing their cricket game on the Oval.

Our walk took us down one street filled with food stalls. The smell of toast and curry came from a panini-maker who was grilling his sandwiches in a press over a coal fire.

Next, the smell of mint and ginger alerted us to the presence of sugar-cane-juice presses. The green juice flowing down from the stainless-steel mill was too tempting to resist. The young man ran the cane through, followed by a second go-through with mint or ginger. It was sticky, sweet, fragrant, green: amazing. We tried several glasses as we walked past them, and our favorite was one that we knew had ice in it, but it was so amazing we couldn’t help but take a few sips.

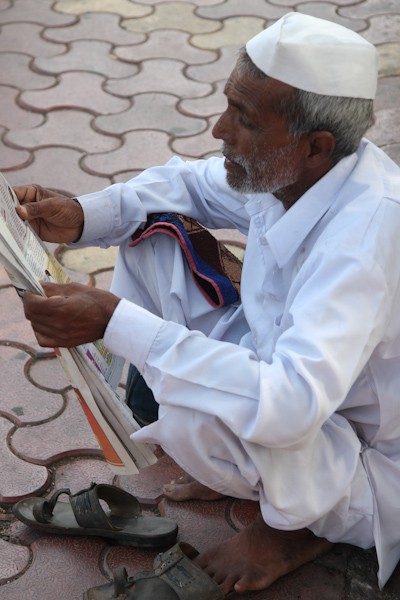

Other than that, we did our best to just enjoy the scene: Locals went about their days unfazed by our presence. Men—and there really seemed to be mostly men—read newspapers with espresso-sized cups of chai, bought breakfast and paan, and commuted on bikes. It occurred to me that though I had looked forward to trying lots of street food on this trip, it wasn’t actually going to be so easy. The risk of getting sick loomed large.

We stopped at one of the better known Irani cafes, Kyani & Company—a 102-year-old landmark—for two glasses of Watermelon juice. It arrived cold and deep red: we feared there was ice or sugar water added (despite assurances) and, though we hated to, we left the glasses behind in favor of bottled water. Nope—I thought—this wasn’t going to be easy; I wanted to try everything!

We kept walking, heading toward Marine Drive—a seaside promenade next to eight lanes of traffic. We had planned to walk along the “Queen’s Necklace” to Chowpatty beach, but—as we got closer—it was clear that the heat was keeping people away and we surmised that the evening food stalls are probably the real draw. We decided, after a look down the shore, that a beach unsuitable for swimming wasn’t the most interesting in full sun (it was just too hot). Instead, we hired a cab and headed for Chor bazaar (or “Thieves Market”)—a site that would be well on the way to our next train station.

The drive there was awesome (except for the whole back-sticking-to-the-plastic-covered-backrest part): we were constantly amazed at the functional chaos of the city and the bazaar district seemed particularly chaotic. Our walk into the narrow, dusty lanes started off well; we were clearly the only tourists around and there was this fantastic stand where freshly fried, non-leavened bread was mixed with sweet orange paste by a group of very nice young men who smiled a ton—except in Aron’s photos (a common theme as smiles and photos apparently aren’t meant to go together).

The bazaar was interesting; we seemed to enter into the automotive-parts section, as we were surrounded mostly by collections of engines, steering wheels, drills, and horns (which they use so often, we thought, it’s no wonder they wear out). But we looked around a bit and both agreed that the general vibe was not what we were looking for.

We caught a cab to the train station and found our platform. Aron got the biggest kick getting on (and off) the train while it was almost still moving–which was incredibly fun to watch.

We stopped at the Juhu station this time and found ourselves in the midst of a food market.

We’ll never forget one stand in particular. Our eyes watered with the smell before they could even recognize that there, in front of us, sat not a pile of beans but in fact a pile of chilies.

Not wanting to miss out completely on the Marriott’s amenities, we ran up to the concierge lounge and put together a small lunch, and then changed into our bathing suits. The pool felt like heaven.

Udaipur

After too short a time, we left for the airport to fly to Udaipur. We had to have our e-tickets converted to paper ones to enter the terminal; we kept our elbows out as we waited in line at the first check-in point after learning that open space is an invitation for someone to cut the line in front of you. Every little detail of the process that followed amused me: I was told I couldn’t take my water bottles and started to down one, when security directed me to the female screening line and said “maybe she won’t mind–just ask.” She told me to drink more of the water while patting me down with the wand. Not really sure why, but I got to bring the other bottle full after drinking from the one. Once inside the waiting area, I sat back and watched them deal with Aron, in the men’s line. Each passenger steps on a box for the screening. I tried not to laugh too hard when Aron got on the box and everyone craned their necks and paused to exchange bemused smiles. Aron, meanwhile, was left standing on a pedestal. Thirty minutes later, the plane pulled up and we all scrambled to board. Again, more looks when Aron bent nearly fully over to enter the small plane.

We both fell asleep almost instantly and, suddenly, we were in Udaipur.

We later learned that this airport was the one shot in Wes Anderson’s Darjeeling Limited. In fact, it turned out that we followed the path of the characters in the movie more than we knew.

A pre-paid, 450 Rs taxi-ride brought us to our hotel, but only after a harrowing ride where we all but kissed other cars. Motorcycles zoomed by, carrying ladies whose saris ballooned in the wind, their colors flying dangerously close to the axles. When our driver changed lanes, cutting off motorcyclists, he would explain in annoyance: “Helmets are their problem. They lose all peripheral vision.” But of course.

It was around sunset as we drove through the smaller villages. It felt so far away from Mumbai.

Pulling into the narrow streets of the old city was quite a crazy affair. The light had grown dim enough that the bright glare of headlamps were jutting in and out of view. Each street seemed more busy than the one before, as three vehicles (our taxi, a moped, and a rickshaw) squeezed through was might pass as a narrow sidewalk back home.

We pulled up to a covered walkway, labeled with our hotel’s name, Jagat Niwas, and tried to tell our driver that there was no need for him to accompany us in. We had read so often about drivers attempting to collect a commission that we were on guard–fortunately for no reason.

Although he was disappointed to learn that we had already arranged a driver for subsequent days (and I’m sure he would have been a relative bargain).

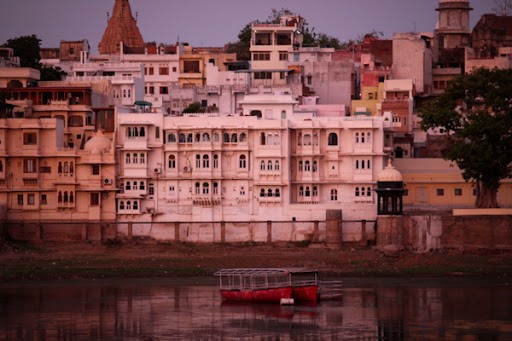

I’m not sure either one of us knew what to expect, but we were happy when the path opened to a lovely inner courtyard: clean, white plaster walls studded with colored lights and filled with ornate wood furniture. Two havelis on the lakeshore had been converted into the guesthouse. We were shown to our room which, modestly, had two beds, and sported a large bay window seat with a view out to the lake and the lake palace.

It was dark, but we could see that the lake was low, but present–we had feared that it would be entirely dry at this point in the season.

That night, we decided to stay close and go to our hotel’s roof for dinner. There was a strong, cooling breeze and we had some wonderful curry while we watched the fireworks that were set off to honor our arrival. Okay, that last bit’s not true. Actually, when VIPs stay in one of the very expensive lake palace rooms, the palace often sets this up, but we enjoyed it nonetheless! Aron swore he saw some huge bats flying around the lake, but it seemed to hard to believe.

Partially due to jet lag, partially because we were excited to get another early start, we were able to watch the sunrise off the lake. Women slowly made their way down to the shore to wash their linens; men joined–more often to tend to their personal grooming. After some cool lassis and some eggs, we headed off to explore the town. The logic of being active near sunrise, then taking a mid-day break at peak sun, was something that apparently appealed only to us. The city was quiet and most stores were closed. Every now and then someone would ask us where we were from–sometimes, it seemed, just to show us that they knew the phrase, and sometimes as an introduction to their shop.

In general, and not just because of the early hour, we felt as though we were the only Western tourists around. Perhaps it was because we visited during one of the hottest times of the year–although we didn’t find it to be too uncomfortable.

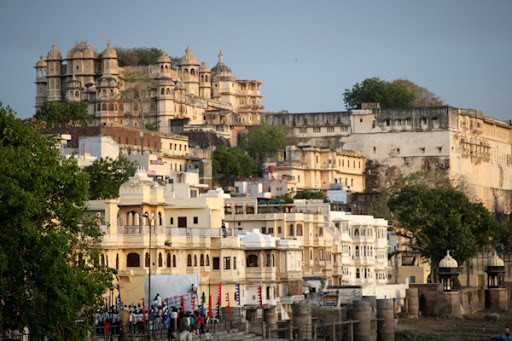

We looked around and scouted for activities for later in the day, crossing over to the other side of the lake to look at one of the open temples and to look back on our haveli and the City Palace.

We were inspired to do some more shopping and wandered around the maze of streets. We passed many tailors who seemed excited at the prospect of making Aron a shirt–commenting on how much cloth it would take.

We did stop into a music shop (Prem) where a charming man who goes by Bablu (actually named Rajesh Prajapat) played the Sitar for us, and introduced us to the singing bowls. They were so beautiful; we couldn’t help but get one of the small ones for ourselves (and his CD).

The James Bond movie, Octopussy, was filmed here and many of the restaurants hold nightly showings. The signs urging you in for Octopussy always looked a little dirty–especially depending on the accuracy of the grammatical context–and made us giggle more than a few times along the way.

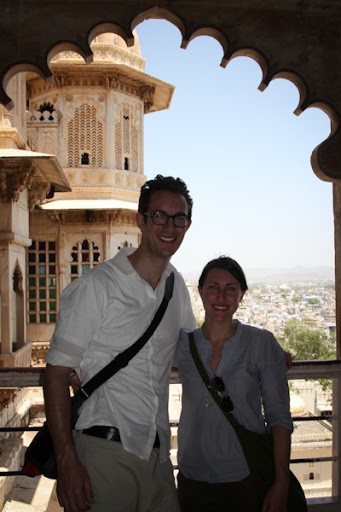

We reached the City palace (which had been closed in the morning for school), and decided to take a guided tour. We debated whether it was worth it, and had to remind ourselves that it was about $3. It was more than worth it. The tour was on the long-side, but considering that it was our first encounter with the Rajasthan culture, there was a lot to learn. We were impressed by how proud our guide clearly was of his town and its history. He also got a kick out of teasing me, and had a good sense of humor.

Starving after two or so hours of touring, we decided to travel outside the old city to go to a restaurant about which we had heard good things: Natraj Lodge. We caught a rickshaw and zoomed past busy markets brimming with brightly colored fruits and women in brightly colored sarees, carrying bundles of greens and clay pots with water atop their heads. At one point, we passed of line of women working roadside, digging a trench–all the while still in colorful saris.

We turned just off the main road, and joined some surprised looking Indians for Gujarati Thalis (a police man even asked us if we needed directions or help). We were seated upstairs, tucked into the corner (out of the sight of the locals?)–I noticed only men were downstairs, but am not sure if it was just a coincidence or intentional. For $1 each, we were treated to an all-you-can-eat lunch. A series of metal dishes were placed in front of us and men strolled through the room with pots of food, refilling, or in our case, filling our plates with wonderful smelling foods. We tried to observe how to eat the dishes from those around us–a combination of hand and spoon which was easy to adapt to, if somewhat messy. I was pretty excited to practice my right-hand-only eating skills. We would barely make any progress before our plate was refilled with fresh, hot food. There was one man with mini-pakoras who came by more often than necessary; I think we were a bit of a novelty.

After lunch, we decided to walk for a while; we had passed so many interesting things on our drive. One of our hopes was to bring home a pair of gold-handled scissors and we found a storefront where a man was sharpening those that were brought by. We asked if he had any for sale, but the only ones he had were giant.

It was blazing hot in the sun, so after a stop for fresh juice and yet another giant bottle of cold water, we negotiated a rickshaw ride back to the hotel. The driver kept letting others hop on during our ride, so we eventually decided to abort and do a bit more walking. We found ourselves in a maze of fabric shops and I settled on a bright yellow swath at one of them.

Dodging pack mules and endless scooters, we went back to the City Palace–our entry passes were still valid–and walked through the grounds, past the Fateh Prakash Hotel and the area where the Royal family currently lives, and toward the Bansi Ghat, the boat jetty from where we would go to the palace on Jagmandir Island.

As we were headed back, single-file to avoid cows and oncoming rickshaws, we were stopped by three people with TV cameras. It turned out that they were a French-Canadian film crew making a documentary about India (Shanti: Au Coeur de L’Indie, for Evasion TV), and they were looking for tourists to interview. Aron and I, with a few more nerves on my part than his, agreed to a brief interview. A small crowd gathered to listen, and a few asked that we take our own pictures of their babies, whose eyes had been rimmed with black makeup. One man owned the shop next door, where students of the miniature painting technique–a pride of Udaipur–showed off their work. He seemed happy to share just the techniques with us, showing that the brush is often made from a single chipmunk hair and the paints from ground-up minerals.

We walked under scores of fruit trees and each was dripping with giant fruit bats. Aron was right: there were bats the night before. And now there must have been thousands! I enjoyed seeing them all, but was glad they were more interested in sleeping than in flying about.

The prince had driven past us earlier, when we were in the main palace complex, and we passed each other again on the island. As his boat came speeding across Lake Pichola, we watched men rush down the dock to greet him. We didn’t stay long on the island, but the views were nice–especially those of the men fishing the waters against the low sun.

We took a short break in the afternoon to enjoy some mangoes we had purchased on the street. A colleague’s main advice to me was to eat as many mangoes as I could while there–we would be visiting in prime season.

That evening, we strolled through town again–stopping to admire batik blocks and more market stalls–and went back to the temple on the other side of the lake that we had visited that morning. We had beers and dinner and watched the buildings opposite grow amber and then pink as the sun set, until they were glowing with lights in the darkness.

Udaipur to Narlai: Kumbalgarh Fort and Ranakpur Temples

The next morning, while I finished breakfast, Aron ran downstairs to meet our driver–Ramesh Meena–and to tell him we’d be right down. He came back to the table with a big grin: “he’s really young.” Afraid I was going to step outside and see a 16-year-old and a moped, I was really pleased when I saw Shyam–at least 20, standing beside a small sedan, with a couple of cold bottles of water and a very pretty bouquet in hand. Shyam, we learned, is a friend and employee of Ramesh (who we’d found highly recommended on the Fodors forumn); at first we were a bit dismayed about the switch, as Ramesh had never indicated that it wouldn’t be him who would meet us–but Shyam turned out to be all that we hoped for.

Our first stop was about 50 miles north from Udaipur: Kumbalgarh Fort. The drive–which I think took about an hour and a half or two–was fascinating. We first passed through what appeared to be the more uppercrust suburbs of Udaipur—where locals jogged and strolled along a closed street—and then joined the highway. Soon after we sped up, the highway became a divided one. No matter: moments later, there was a very beautiful truck headed straight toward us. We felt this to be particularly emblematic of the “there are no rules except to stay left” attitude we encountered when it came to driving.

The ride started alongside motorcycles, and moved into more rural areas, where the traffic moved almost entirely on foot: camels carrying loads of straw, women with bowls of greens atop their heads, men with staffs—walking with families in tow, and cows—always lots of cows. We would occasionally pass through a small village, where we were likely to see a bus being loaded from all sides with people and goods, but most of the roads were fairly quiet. We stopped at one point to watch some black-faced langurs (they watched us right back), and it seemed we could have stayed parked in the road for some time without another vehicle needing to pass. The rest of the time we were winding through the hills.

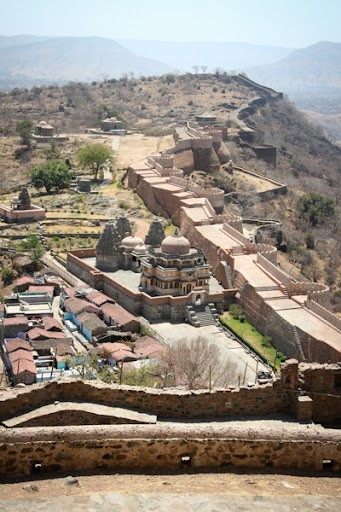

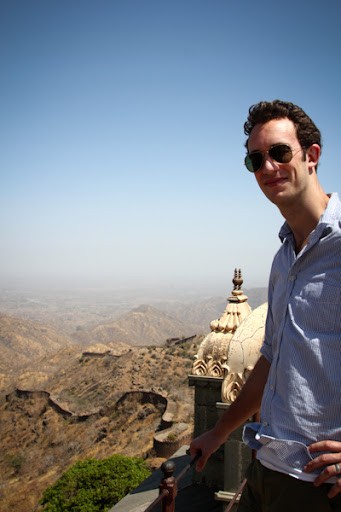

Kumbalgarh Fort appeared oddly suddenly—the first view sort of threw me: stunning! Because it sits within the Aravalli Hills, it wasn’t until we were pratctically at its gates that it came into view—especially surprising considering that its walls extend over 22 miles (and, at places, could fit eight horses abreast, as you’re sure to hear). The fort belonged to the Mewar Kingdom (which included Udaipur) and sits on the border of Mewar and Marwar. It’s a vast place, containing over 350 temples.

We appeared to be the only people there—-a lone officer handed us our tickets and sent us through. We quickly picked up a friend, a sort of sad, sweet dog who followed us into one of the temples and through its open corridors. He seemed to be leading us on a tour–but failed to warn us about the bats that hung out in the shaded corners.

And we met more critters as we climbed up to the top of the fortress: a family of Langurs spotted us before we caught sight of them and started running–in leaps and bounds–across the grasses, from the upper walls to one just below where we were standing. We snapped a photo and then slowly walked toward where they had all positioned themselves. Again, with incredible speed, they started climbing down the tall outer walls. After one last glance up toward us, they disappeared–and seconds later they had scaled the huge walls and crossed the valley floor.

After leaving the fort, Shyam took us another hour or so along to the enormous Jain temple complex of Ranakpur. He suggested a stop for lunch along the way: delicious butter paneer, more freshly made parathas, and sweet lassis. It was a nice break.

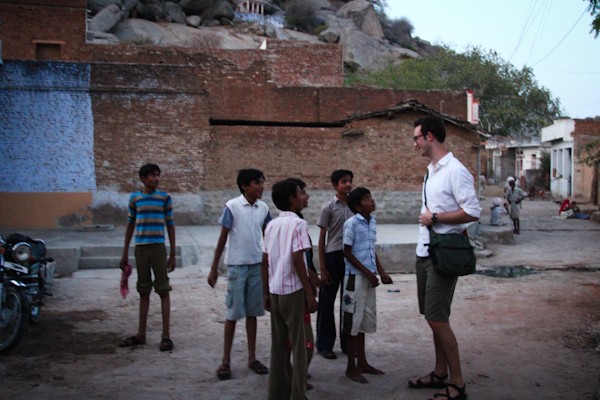

After changing into long pants and leaving his leather belt in the car, Aron and I made our way into the complex. Our first stop was at a smaller temple, where three small children greeted us with blessings and squirmed with excitement when we took their photo (though their serious poses might not suggest so at first glance).

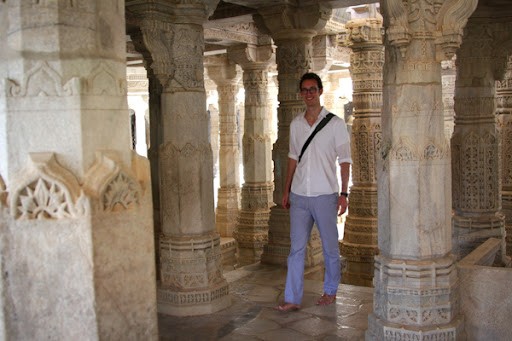

Kumbalgarh was an impressive site–so huge and insurmountable. But Ranakpur was really the highlight of the day; it was amazing.

Leaving our shoes at the base of the temple was a little scary: the ground was so incredibly hot! Even with the carpets out to connect you from the shoe drop to the temple’s interior, it was hot for the unaccustomed sole.

Ranakpur is one of the most important Jain temple complexes—and it was clear why. The main temple, built in the 15th century, is made completely of marble. The halls are supported by over 1400 intricately carved pillars, none of which are the same. Jains believe in doing no harm to animals, to the extent that priests—who wear all white—will cover their mouths to avoid inhaling insects. The contrast of the women, ever so coloful, with the milky-white marble and white-clad men was so beautiful and we couldn’t help but take photo after photo. As it turned out, many(women in particular) expected this of us and would conveniently pose themselves in our paths—even while sometimes shielding their faces. Throughout our trip we were armed with rupees, in the case that one of our subjects asked for compensation, but only once—a young girl in Udaipur–did anyone ever ask. I wondered what their interaction had been with other travelers.

Narlai

From Ranakpur, it wasn’t far to the village of Narlai. Shyam told us that he had never been there before (most of his passengers travel between Jaipur–where he lives–Agra, and Delhi). I never saw him look at a map (and certainly not a GPS device), so I’m still wondering how he navigated those roads.

We drove through the small village—twisting and turning through the streets as cows stood in the middle, like statues. Another animal added to the sense of our being on an obstacle course this time: Narlai appeared to have a sizable population of wild pigs, covered in spiky, black hair.

Aron asked Shyam if pig is ever part of the cuisine, to which he replied “no,” with some surprise at the question. Aron then said: “Italians love the pig.” “Really?” “Oh, yes.” I’m not really sure what brought us to the Italian tangent, but good to know!

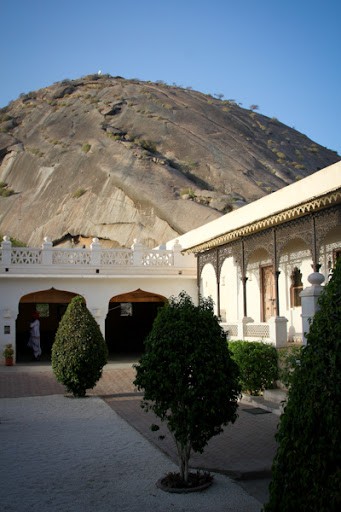

Our hotel, Rawla Narlai, stood out for its bright white outer walls and large wooden gate; we were happy to hop out of the car and stretch our legs. The place—a former hunting lodge that once belonged to the maharaja—was beautiful, and they greeted us with glasses of lime soda and cool towels. The men who worked there were dressed beautifully, with bright red turbans and pressed, embroidered whites. I suddenly recalled the photos I had seen of such traditionally dressed men: I had been turned off at first by hotels featuring such photos, afraid of being surrounded by people dressed in costumes for tourists’ benefit. By the end of our time in Rajasthan, Aron and I were both laughing at ourselves for not understanding just how many people would be dressed so traditionally. Granted, the men at Rawla Narlai seemed to be wearing the special-occasion version of the clothes we’d seen worn along the roads, but I’d completely underestimated the extent to which such seemingly special outfits would be on display.

We checked into our room—the blue room (blue accents and a view of the blue pool, it was explained)—and decided we’d earned some relax-time by the pool. We peeked around the grounds, ordered some beer and water, swam a few laps—heavenly—and chatted with an Englishman who had recently relocated to Delhi, before deciding that we should get dressed if we wanted to climb the large granite rock overlooking the hotel before the sun set.

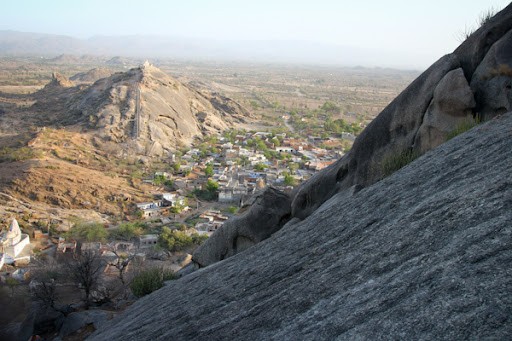

We asked how to get to the steps and there was a surprising degree of insistence that we wait for someone from the hotel to come with us—and the other guests who had planned to take the walk just then. Six of us made our way through town and climbed the 750 or so steps to the top. The rock is dotted with temples and we paused to honor a deity and hear a prayer drum echo on our way up.

The views looking back at the town were incredible. Our guide from the hotel explained that Narlai is a holy town, and we could see now that nearly every road seemed to lead to a temple. The intricate Jain temples stood out most.

We found our climbing companions quite distracting, so we did our best to hang back or climb ahead, and discussed later that there was no real reason why one couldn’t make the journey on his or her own.

Despite that, however, it was the perfect time to go. It was warm, but there was a nice breeze and the trail was shaded on the way up. We reached the top and found wild peacocks—the bird of India—there to meet us! A large elephant-statue faced out over the town, which seemed lit up by the setting sun, and we drank some tea from our guide while looking out over the town and the desert beyond before climbing back down. Lovely!

As we made our way back toward the hotel, our guide seemed concerned with keeping us together and slightly unamused by our constant stopping to take photos or to exchange smiles with the town’s residents. Not wanting to distress him, we followed him back, saying ‘thank you’ and handing over a small tip before heading back out on our own. We saw Shyam—who handed us a cell phone so that Ramesh could confirm that we were happy and that everything was going smoothly. While Aron was affirming, I was trying to capture photos of cows and, in the process, drew the attention of some very cute children. One kept wanting his picture taken with his shirt lifted to show his undershirt—-I wonder where he picked that up!

It wasn’t clear to us where one would have dinner other than at Rawla Narlai. The meal was expensive by Indian standards, but the setting couldn’t have been nicer.

A table for two had been set up for us near the pool, with the temple-dotted rock glowing in the distance and a sitar player playing nearby. Candles had been lit around the property, and everything looked beautiful. Dinner was a decadent version of a Thali. My favorite was a coconutty Okra–I think the man who served us was excited for us to try that one, too.

But halfway through the dinner, two of the staff came by to place a third chair at our table. The owner of the lodge came over and sat down with us. At first it was very nice: we got to learn about how his ancestor had rescued the Maharaja such that the lodge was transferred to his family, and he told us about his experiences running the hotel. Unfortunately, the conversation started to feel a bit too much like a customer survey, and we regretted that we weren’t left to enjoy the romantic setting on our own.

On that note, I will say that–in reflection–India was romantic by nature of our attitude toward one another and by virtue of our exploring a new, exotic place together; but I don’t know that it would be the first place I would suggest for a honeymoon. As I mentioned, we often felt compelled to walk in single file on narrow streets; avoided holding hands or showing affection in public fearing it would be inappropriate; and we were often exhausted by the end of the night.

Which is probably because we couldn’t help but want to get up with the sun each day. I sort of loved the schedule we kept, to be honest. The next morning, after a very British breakfast (Marimite, anyone?), we snuck out to walk around the village on our own (in spite of the owner’s suggestion the evening prior that we go with one of “his boys”).

Our walk that morning is one of the highlights of the trip for me. All we really did was wander, but we encountered such warmth and interest. We would ask if we could take a photo and would become engaged in a game of show-and-tell. Women who at first would appear shy–coyly pulling a veil across their face to conceal a smile–would pose and then ask to see the result. A couple of times they would ask us to reshoot the image–a chance to improve their portrait.

Old men, in hot pink turbans, gathered to pose. One older man whose picture we took (again all smiles until the shutter snapped) spotted us again later, while he shared Chai with a friend, and motioned us over to take another picture of the two of them together.

A family offered us dried coconut from their kitchen, and others pointed to things we might find interesting: their bicycle tire, a treasured cow, their baby sister. The children were a lot of fun–so wide were their smiles.

It feels wrong to always speak in the negative about my expectations, but I found the most remarkable thing to be how often I was pleasantly surprised. Where we feared despondence, we found enormous joy. It feels naive to assume that these families, with their bare single rooms, had all that they needed to thrive, but they certainly did remind us how basic our needs really are.

Another highlight was stopping into a bracelet shop: everywhere we went, we saw women with plastic bangles pushed up their arms to varying degrees. Some seemed to be adorned with white piping, whereas most wore an ample number of the shiny plastic rings that lined the walls of many shops. I picked three gold rings out (and learned that their sheen was derived from gold-colored tape); a young girl—maybe eleven years old—struggled to push them over my sweaty hand and onto my wrist. I felt bad about how slippery my palm was and looked at her apologetically. Neither she nor her grandfather seemed to know how to charge us, so she ran out to bring her father in. I think we spent under a dollar, in the end. I loved them and felt I endeared myself to other women at other times during our travels thanks to them. Meanwhile, Aron and the grandfather had nearly the exact same glasses (the thick plastic frames favored here are in vogue throughout India—without any nod to the past, however, is my guess), and sat to pose for a photo together.

We went back to the hotel for one last swim. And a turban tutorial. We asked one of the staff about his turban and how often he simply lifts it off versus re-composing it. I’m not sure he ever answered that exactly, but he demonstrated how easy it was for him to tie. It was amazing how much cloth he twisted to create the result.

We settled our bill and met back up with Shyam, who let us know that the staff quarters had been nice there.

One thing we hadn’t gotten to see in Narlai–that we would have liked to–was the

baoli (step well). The hotel will put together an elaborate cart-ride and dinner out to the step well, but we had chosen to forego this. Shyam helped us ask some locals for directions on our way out of town and with some loops and effort, we found our way down a dusty road to a large, elaborate well. Built both for practical reasons (water supply) and for social ones, the step well was quite beautiful. Two men were on the premises and one happily showed us around (walked beside us, smiling and pointing). He was pretty funny about Aron’s photo-taking, seeming upset if I didn’t stop to smile and pose each time Aron raised his lens.

We learned more about Shyam on the next segment of our drive. It was especially interesting to hear his opinions on his arranged marriage. He told us that he had gone from being a young man who thought “no wife, good life” to being completely in love. And “isn’t is nice to know that there’s someone out there that you love and who loves you, too?” Awhhhh, Shyam…

We did have a small suspicion about one stop he suggested—a rug shop just outside of Jodhpur that he said makes the goods that we would find distributed in town—but we still enjoyed the stop, so it didn’t really matter. I think he was probably surprised that we hadn’t asked for help with any shopping while he was with us.

Shyam would have stayed with us the rest of that day, but we decided to say goodbye once we reached our next hotel, in Jodhpur.

27 Comments