In the summer of 2013, a good friend’s father, Rubén Rosales, summited Mount Katahdin in Maine, thus completing a thru-hike on the Appalachian Trail.

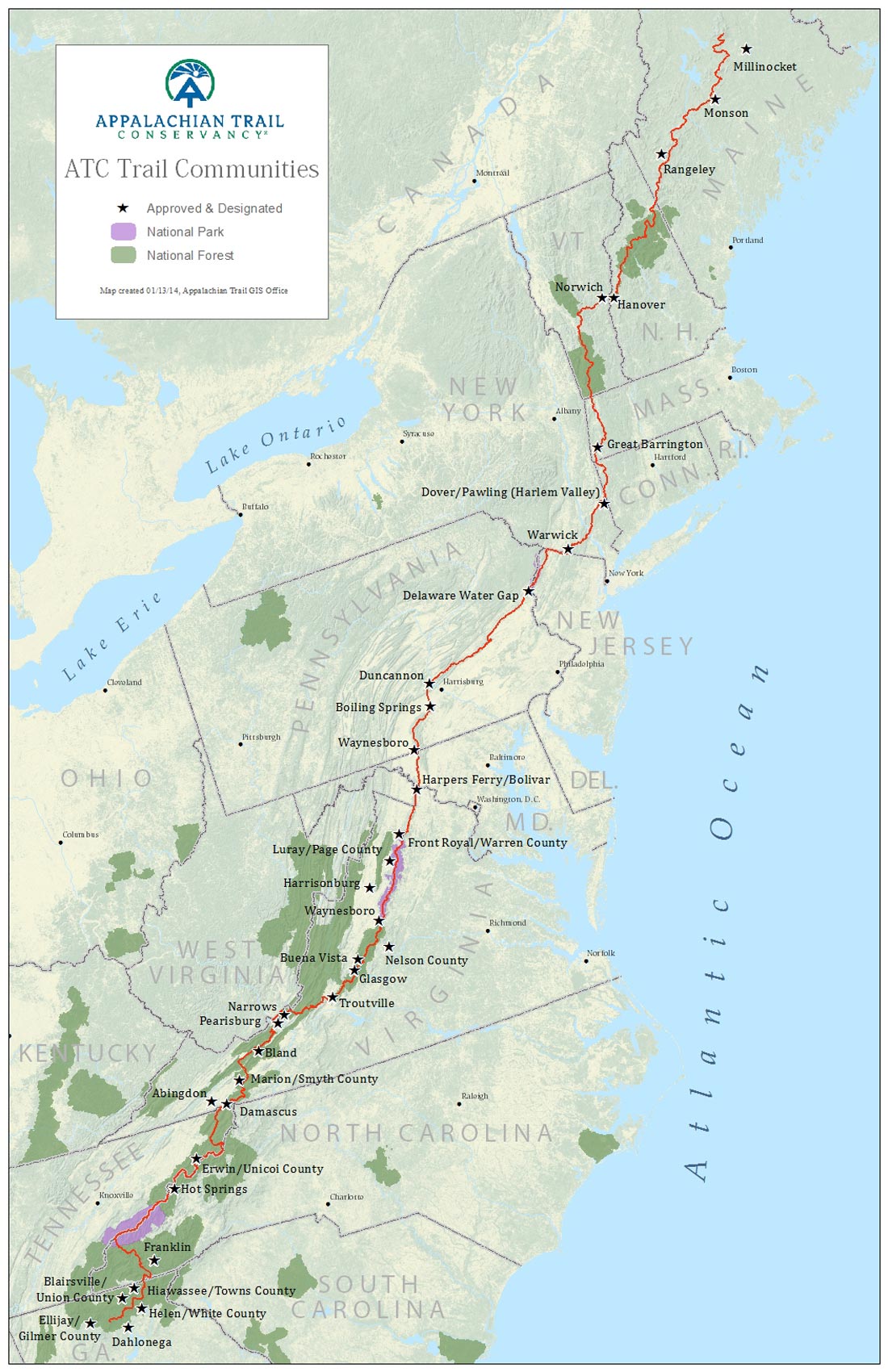

Starting at Springer Mountain in north Georgia and passing through 14 states—Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine—the Appalachian trail (or A.T.) is over 2100 miles long and gains and loses a total of 515,000 feet of elevation (the equivalent of Mount Everest, sixteen times). Rubén spent 6 months and 1 week on the trail, but was away from home for nearly 7 months.

He was 70 years old, and only the 24th thru-hiker in their 70s on record to finish.

Tremendously inspired, I asked him to sit down and tell me what it’s really like to thru-hike the A.T. …

On deciding to do it…

“I spent 42 years in very intense, demanding, international work. …Finally I decided to retire. I gave 18 months notice. My biggest issue was ‘What am I going to do… with my life?’ ‘Play golf?” … “I felt like I needed to do something extraordinary to transition to retirement.”

On choosing the A.T. …

“I had three reasons to do the trail:

“I had read in the late ’80s about these two guys who had sold their companies and decided to do the Appalachian trail. I thought, ‘That would be glorious.’ Getting away from everything. That resonated with me.

“And I really wanted to get my health to the next level. Which would really have an impact in my third life.”

Finally, I wanted to “use the trail as a way of thanking people, particularly American people, who had given me a hand. By that I mean, in most cases, just a nice word of encouragement. [For example,] I left Guatemala during a civil war. We lost about maybe 200,000 people. Mostly it was the military against the people. And most of the people that were killed, or disappeared, or murdered were students. So somebody, a missionary, came and said ‘Rubén, you have to go. You cannot stay here.’”

On preparing…

“I’d spent 18 months thinking about it, but I had taken 34 international business trips in 2012 alone. That’s not counting personal trips. There wasn’t much time to prepare. I retired December 31st and spent a few weeks trying to leave everything in order at work, and then I went and bought my backpack and things like that. On February 1st of 2013, I started the trail.”

On that first day…

“I went to Springer mountain in Georgia. You take a plane to Atlanta and someone comes and picks you up in a van and takes you to a hostel about 20 miles away from Springer mountain. (Both the southern terminus and the northern terminus, which is Katahdin mountain, are very isolated.) … I spent a night at this hostel and then the following morning this guy drove me to Springer mountain along forest roads and got me to a parking area. He says ‘you go here, one mile, to Springer mountain. You come back and continue there. I recommend that you leave your backpack in the woods and you just take a bottle of water and go.’

“The temperature in the parking lot was 19 degrees. You go… 1000 feet or whatever up the mountain and it’s cold. To the point that the pen you’re supposed to register with didn’t work! So all I did was take a picture of the registry. I couldn’t even write my name.

So you are… all by yourself.”

“You’re obviously very excited about being there. You know that you are in for an interesting sort of an adventure. And you are not let down at all.”

On filling his pack…

“I was on the trail 6 months 1 week. I’d stop every week to take a shower. And I’d pick up supplies.

“My daughter Melissa was my logistics organizer. I got 34 packages and I didn’t carry a stove. I carried military rations. Every week she’d send me a box of military rations. And, initially, it was so cold that I couldn’t heat them.”

“You spend 6000 calories per day. I lost 30 lbs—I had friends who lost 60. You just can’t keep up with the calories. If you have an intake of 4500, that’s a good thing. [I consumed] most of it passing through towns. Junk food. Nothing healthy. 12,000 calories easily.

And on emptying it…

“I got a ‘shake down’ of my backpack… there’s a place about 30 miles from where you start and you can voluntarily get a shake down. They took 11lbs. They took a camera, an iPad, and left me an iPhone. [But] you seldom had a connection—maybe only on the tops of peaks. Usually I would go into a town library to use WiFi.

I’d put it on Airplane-mode to take pictures and used it to keep a log.”

“I had close to 300 books in my iPhone but there was no time to read. You walk 20 or so miles and get to the shelter and the next morning you’re up again early. It’s like working: You’re up early in the morning and go; and in the evenings you get your water and your meal and maybe chat with people. You’re spent.

“You get more interested in listening to people. And to the silence of the mountains.”

On making strides…

“I averaged about 15 miles per day. And by the time I reached Shenandoah [the most beautiful stretch], I was in great shape and moving very fast. Once you reach 650 miles, you’re like a swiss chronometer. Your body is at its peak.

“But the saying is that it takes 80% of the trail to prepare for the last 20%. Because in New England, everything changes. I’d hit a big wall in the night, and then you have to climb. Mentally, it’s a new challenge. After about three mountains, you get the hang of it technically. But mentally, you’re always challenged.

“The whole thing is maybe half mental.”

For example, “I was hiking with a guy for a while. A perfect physical specimen. It was his third time. And he started to have some issues with his feet. And you could hear him building a reason not to complete it.”

On persevering…

“I got injured. My leg swelled up. I would walk on it and it hurt, but I’d just put it up at the end of the day. But once I got to Damascus, Virginia, a physical therapy guy said ‘you have to go see a doctor.’ They took X-rays and bandaged me up, and I had to keep my leg up for seven days. Still, I spent three more weeks on the trail with two bandages and I had to stop and rest more. It delayed me. It gave me concern about not finishing.

“But that passed. You have to walk through issues like that.

On feeling afraid…

“Because [I’d injured my] leg, instead of carrying my pack all the time, once I got to Erwin, TN, there was a person who would take you ahead on the trail and then you walk back with a day pack. It’s called slack packing. This was about 23 miles and I started to walk but I somehow got lost and I ended up taking an old AT loop. You see, the miles keep increasing because they move the trail out… it had been used too much. I took this 5 mile loop and ended up going the wrong way.

“It was March 22nd, and we had an unexpected storm. And I was at one of the highest peaks, Roan Mountain. The winds were very strong. The temperature was very low. There was so much snow and the minute the snow would hit the rocks, it would freeze.

“I thought that was the end of it.

“I managed to get off there and get to what they call ‘the gap.’ The gap was at 5,800 feet and you could either go to North Carolina or Tennessee. It was snow and ice and because I wasn’t planning on spending the night, I had to continue walking. My water was frozen, so I kept walking. I walked about 8 miles and then saw some lights. It was a truck. I told them I was going to Mountain city to find a hotel. ‘There are no hotels for about 40 or 50 miles. Get in.”

“It turned out he was a park ranger. He turned the heater all the way up, and got on the radio and arranged a cabin in the park.

I had started at 8 a.m. toward Erwin, TN, and this is now four in the morning. The guy said ‘you are so lucky’ he was doing security, ‘this was my last run.'”

On making mistakes…

“In my case, I’d never spent too much time outside. Someone who works outside often has the points of reference that are almost automatic. For me, it wasn’t. I got into the shelter in the evening and if it were 1/10th of a mile off of the trail I’d have to think about it. It wasn’t automatic. I got lost and… you put your life on the line.”

“I really was a neophyte about outdoor life… I hadn’t done much camping. When I purchased the food bag that I was supposed to hang, I chose a green or brown bag with a green cord. And at night I hung my food. And then, the next morning, I couldn’t find it! It took me maybe 30 minutes! How embarrassing! I bought an orange bag with an orange cable at the next town and really memorized where I hung it.

It’s a very unique experience and you’re constantly learning.”

On being in nature…

“You have a blue sky with stars. You’ll hear owls—especially in the mornings. You’ll see Eagles.

Particularly when you are in Maine, there is no interference from towns. It’s just gorgeous.

“When I started it was winter, so bears were hibernating. I went from winter into spring. And immediately you start seeing bears and prints of mountain lions. You see all kinds of interesting things. In most cases they are more afraid of you than you are of them. It’s part of the beauty. The quieter you are, the more opportunity you have. The chances are low if you’re walking and chatting. They’ll hear you from a long distance.”

“But, oh, the bugs! We had lots of storms in very hot weather.

I had 100% DEET and had put it on 3 times already, and wasn’t going to put on any more. But then I looked down and my arm was black with mosquitos. I got eaten through my shirt to the point that when my wife came to meet me in Williamstown, I had infected wounds and had to get antibiotics. They just go after you. And people quit because of that. You’re getting chewed up. You’re walking on the trail in a foot of water. … It can be uncomfortable.

You say ‘this is it!’ I cannot let the trail defeat me. You have to look at the positive.”

On what surprised him…

“People were so open.You don’t use real names. And they were always willing to help you if there were something they could do.”

“On the trail, you weren’t asked what car you drove or even where you lived… on the trail, it was more about ‘what happened today?’ ‘What did you think about this or that?’ It was all related to the AT.”

“Most of the time, when you’d get to a shelter you’d find people. Sometimes three or four. Sometimes more. But there were days when you didn’t see anyone.”

On missing family…

“When you say ‘Katahdin,’ you picture your people there. You have motivation. You obviously miss your wife and your kids. But the grandchildren… I didn’t have doubt that I would make it, but having [my grandkids], those two young ladies to think of… that’s important and helps you do it.”

On coming home…

“There was maybe a month of so when I would dream about being on the trail. You don’t dream about the pleasant things, but rather the challenges. I’d be close to losing my footing, or something like that. I’d wake up and be glad to not be there.

On who does and should do it…

“Conventional wisdom doesn’t allow one to really understand what it takes. But I would recommend it to anyone who has a spirit of adventure.

“25% of the thru hikers are women. 60% are in their 20s. 4% in their teens. The rest are above. And the longer you wait, the more difficult it becomes. Your body is really challenged to the Nth degree. But people who have done it in their 20s often do it again.”

“Most people have their reason: They’re looking for an answer. Looking for a light at the end of the tunnel. They’re searching for something… a trigger, a new direction… to achieve something else. Every one has their reason.

“My objectives were very practical, but what I got was an appreciation for nature. An appreciation for preserving nature. For fighting, in a sense, to preserve certain areas of the world. Not from getting oil or having big apartments… but really preserving in a natural state. You can see where somebody lost the fight in many places around us.

“I’m now very active with the AT conservancy.”

“Once you do it, it becomes a part of your self. Don’t ask me why. It’s almost like an itch… I’ve done a few hikes now with the Sierra club and it’s just fantastic. And [hiking and being outdoors is] now second nature, whereas before it was foreign. I was very concerned about doing things ‘right.'”

On learning what one needs…

“In our normal life, we want so many things, but we need so little.

Everything I actually needed was in my backpack.

“This rudimentary life… the lesson is that you can live without much. It’s a very simple, highly satisfying life.”

Thank you so much, Rubén! You’re an inspiration!

P.S. Other inspiring through-trails and long walks, and perhaps the most well-known (or at least the funniest) book about walking the Appalachian Trail.

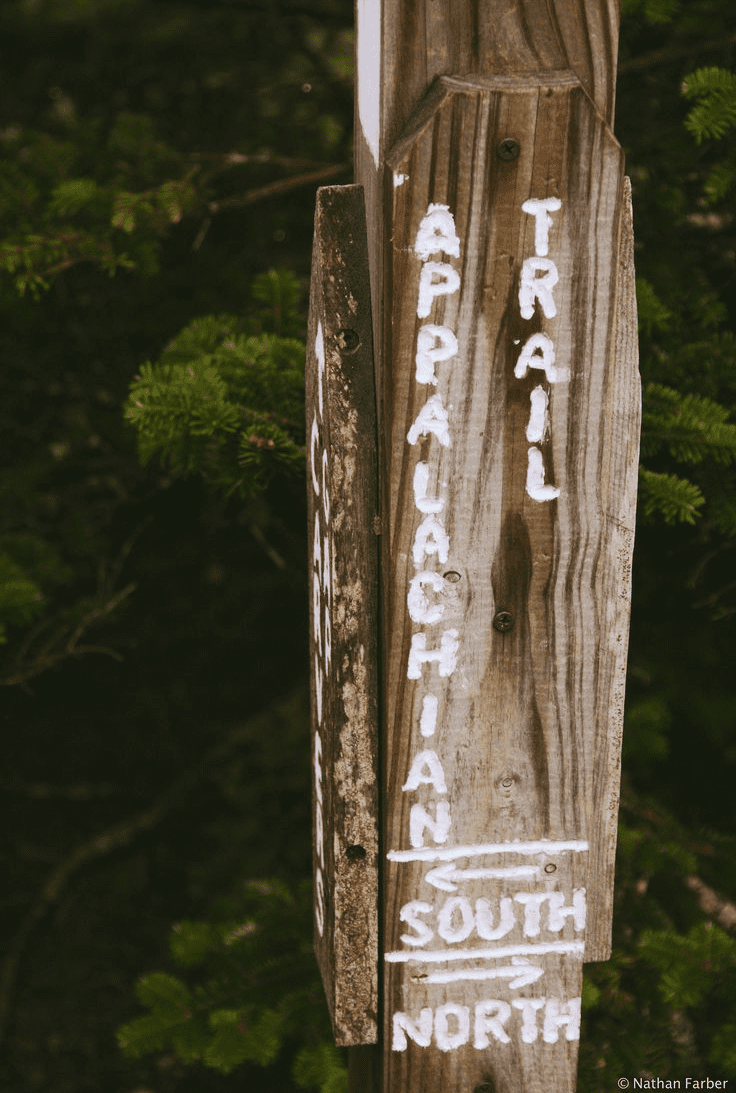

Top two photos of Rubén by Chris Gallaway who met Rubén along the route and took these photos for his documentary, The Long Start to the Journey. Bottom are courtesy of Melissa Neff. Additional Images: Flume Gorge, New Hampshire by PinkCarStops / AT Map / Camping Beneath the Milky Way by Jon Beard / McAfee Knob Overlook via (photographer unknown) / Trail Marker by Nathan Farber

*Editor’s Note: All quotes are directly from my interview with Rubén. However, statements have been arranged out of order for narrative purposes.

26 Comments