Hannah and I have been online friends for years now. We both contributed an interview to a series called Boarding Pass on Anne Ditmeyer’s blog, Prêt à Voyager, and I’ve been following her since—often to see what how she’s styling her incredibly chic hair (since cutting it short); often to see where she’s going with her incredibly charming girls; and always to find out what she’s reading. I’m thrilled that she agreed to share some of her recent favorites and talk about being a reader…

Reading After Kids & The Art of Auto-Fiction

By Hannah deBree

My friends and I have this ongoing conversation about how our brains changed after having kids. In general, we get less sleep, we are required to provide solid answers in meaningful conversations (every. single. day.) about what happens to bodies after people die and who was the first human and why don’t birds have hands, and we are multitasking jobs and families and groceries and romance more than we ever knew was possible. The truth is, it takes a lot of brain power, like never-ending brain power, to be a parent.

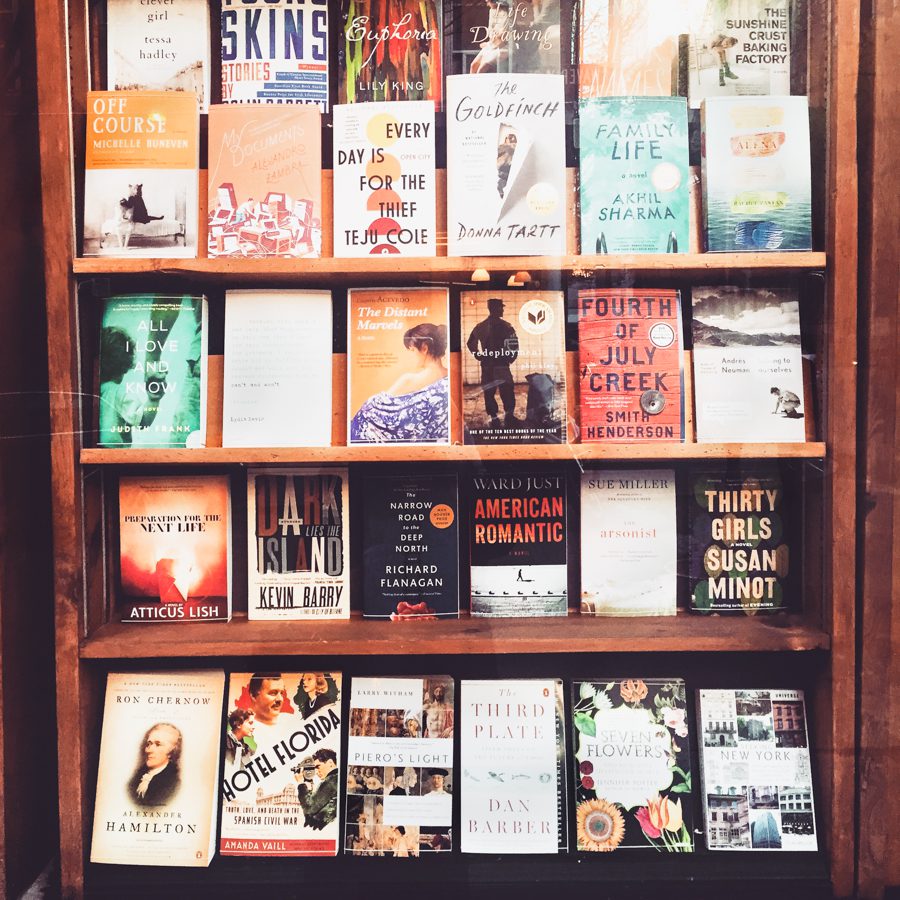

Before kids, I was an avid reader, sometimes finishing three to four books a week. Seriously, what a luxury to have all that time! Some weeks I’m winning if I get a few chapters read, and there are days I feel lucky if I have the mental space to read at all. Though I don’t read with the voracity I used to, I still think of myself as a reader—even if the act of reading has changed. I used to be able to focus, block out the noise in my brain, get lost in a book for hours on end. Now when I read, the focus isn’t always as focused, the noise in my brain remains a dull hum of tasks to be done and items to add to the grocery list, and the time I spend reading is mainly at night when I am my most tired self.

But the act of reading is, in itself, a freedom, an escape from the present tense, a journey for my brain. I might open a book distracted and exhausted, but at the end I feel as if I’ve restored a bit of that brain power and am glad for the break.

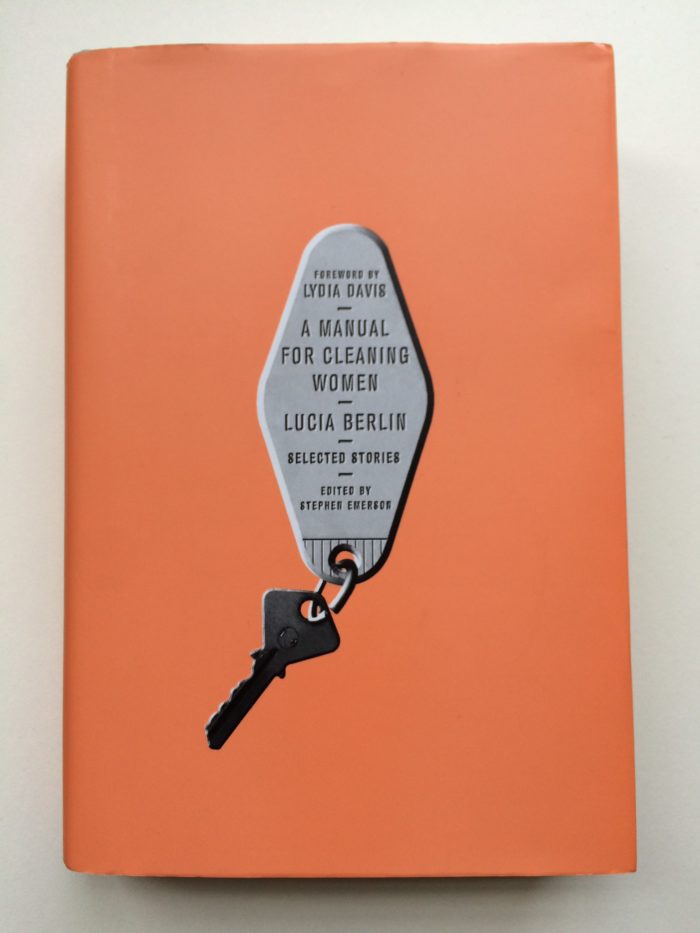

Recently, I’ve found myself escaping more and more into autobiography and “auto-fiction,” a term I discovered while reading Lydia Davis’ foreword to Lucia Berlin’s fantastic book of short stories, A Manual for Cleaning Women. In her foreword Davis writes:

Although people talk, as though it were a new thing, about the form of fiction known in France as auto-fiction (“self-fiction”)—the narration of one’s own life, lifted almost unchanged from the reality, selected, and judiciously, artfully told—Lucia Berlin had been doing this, or a version of this, as far as I can see, from the beginning, back in the nineteen-sixties. Of course, for the sake of balance, or color, she changed whatever she had to in shaping her stories—details of events and descriptions, chronology.

Berlin’s short stories are accessible, funny, sad, and raw. Her characters move through transient worlds—buses, laundromats, hospital rooms—and have intimate conversations and mundane experiences that seemingly take them nowhere, but somehow leave the reader with the feeling she’s been taken somewhere. The intersection of Berlin’s own life and those of her characters is indiscernible to the reader, but it is clear her personal experience shape and define the roles of her narrators in brave and formidable ways.

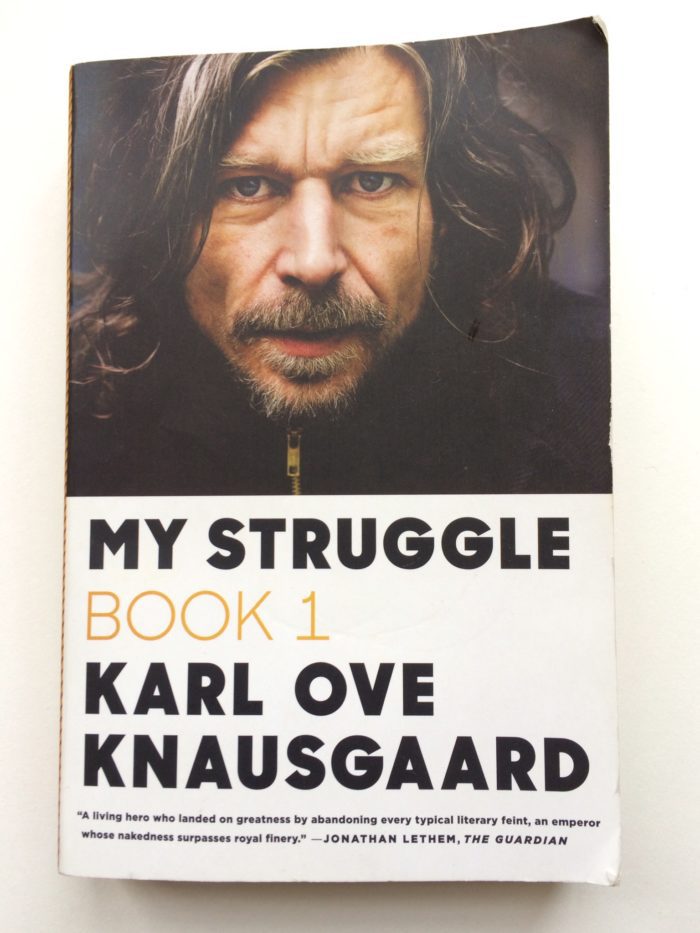

If Lucia Berlin’s stories are fiction with a grounding in personal history, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s massive My Struggle, the first volume in a series of six, must be autobiography built on little fictions. Memory is a faulty thing, and the act of writing one’s story is an exercise in recollection. The heft of My Struggle can be off-putting, but don’t let its size discourage you from reading it. Knausgaard’s book, a meditation on death—the big death we all face and all the metaphorical deaths along the way—and memories of growing up in Norway is intensely readable. His struggle is that of an ordinary man: the desire to be both accepted and to stand apart, to be validated by a parent, to make sense of the monotony of child-rearing, to create something original and new, and to bear witness to life as it bucks, surprises, falls short, and renders one mute.

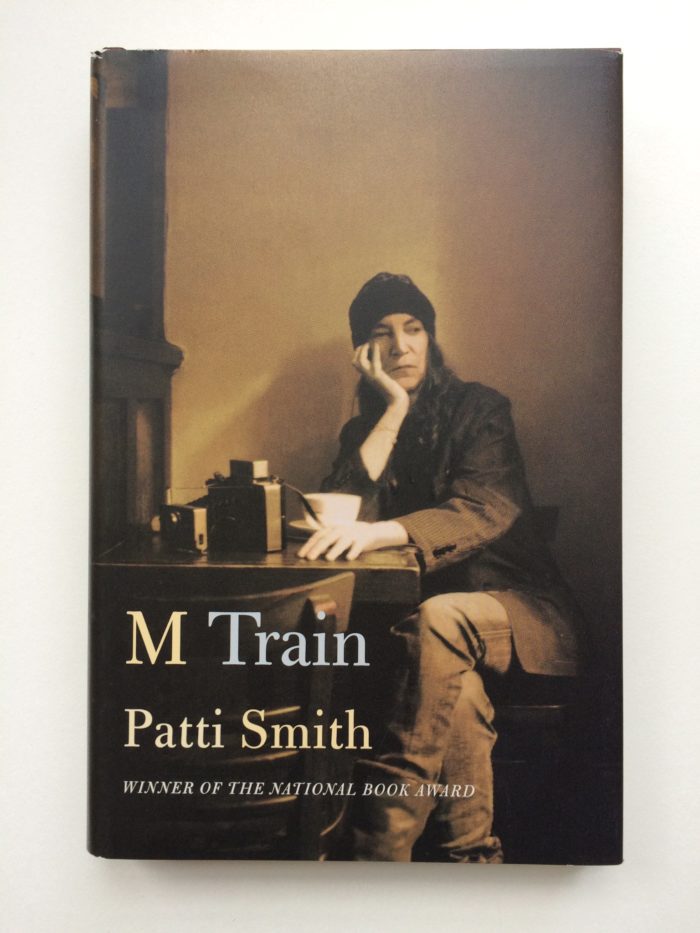

It’s fascinating to see how writers translate their lives into narratives, from sentence into paragraphs, constructing separate lives from personal experience. On the subject of losing loved ones to death, Patti Smith, musician and author of M Train, told NPR, “they are all just stories now.” As if the people and the emotions, the highs of love and the pains of loss, when written down, are given their own space and start to exist outside memory. They are captured in book form. I became enamored with Patti Smith’s writing when I read Just Kids, the beautiful coming-of-age portrait of her relationship with artist Robert Mapplethorpe and tangled romance with New York City. It is a true pleasure to read anything she writes.

I could go on and on… Maggie Nelson’s brilliant and profound study on motherhood, love, feminist theory, and gender identity in The Argonauts…

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ exceptional letter to his son: a must-read examination of racial injustice, systemic oppression, and the war on black bodies in Between the World and Me…

Helen Macdonald’s fascinating memoir following the sudden death of her father and her attempts to tame nature when she adopts and trains a goshawk in H is for Hawk…

But, I am, as always, short on time.

What books are you escaping into right now? Do tell…

Happy reading!

Thank you, Hannah!

When Hannah is not reading, she is busy raising two confident and hilarious girls in Oakland, California. She is also the director of marketing + social media for Illustoria, a magazine for creative kids & their grownups, launching in Summer 2016. You can find her on Instagram.

18 Comments